Most AI agents fail in production not due to lack of intelligence, but because they are trained in RL environments that don’t resemble real software. To become reliable, agents need environments that scale, evolve over time, enforce causality, and provide verifiable outcomes. Abaka AI builds RL environments that push back—forcing agents to adapt, recover, and learn under real-world conditions rather than curated demos.

Why Agents Need Real RL Environments That Push Back

Why Agents Need Real RL Environments That Push Back

Over the past year, AI agents have dominated the demo circuit. In tightly produced videos, they glide across dashboards, complete multi-step workflows, and operate productivity apps with a kind of polite determination. These demos spread fast, in part because they suggest a world where software finally operates itself.

But developers who try deploying these systems in real environments tend to experience something different.

The moment agents leave curated demos and enter everyday software, they hesitate. They misread states. They click too early. They wait too long. They fail silently. In short: they behave exactly like systems trained in a world that never quite resembled the one they were meant to work in.

What’s becoming clear—across research labs, startups, and enterprise automation teams—is that the problem isn’t intelligence. It’s environmental realism. Most agents are trained inside oversimplified RL environments: controlled, synchronous sandboxes that hide the complexity of real software. Real applications are anything but controlled.

As more teams confront this gap, a new consensus is emerging around what real RL Environments for agents must provide in order for learning and deployment to converge.

The Three Requirements for Real-World Agents

Across the industry, three needs appear with near-universal agreement:

- Agents need environmental scale.

- Agents need a sense of time.

- And engineers need evaluation they can trust.

These aren’t idealistic principles. They’re survival requirements—conditions without which agents remain demo-native creatures, not production-ready systems.

Scale: Where the Real Failures Live

In demo environments, everything loads predictably. Error states are predictable. Flows are linear. That world is good for showcasing capabilities—but ineffective for building robustness.

Real interfaces, by contrast, are patchworks of legacy design decisions, network quirks, region-based logic, caching layers, and UI behaviors that only appear under specific account or session states. When agents trained on a single interface encounter one of these variants, they don’t degrade gracefully—they simply break.

Teams that test agents across hundreds of apps have observed a consistent pattern: after enough variety, agents stop memorizing interface positions and begin detecting structure. They learn the logic behind flows rather than the layout of specific pages. And they improve most dramatically not in common cases, but in the long tail—precisely where real software spends most of its time failing.

Time: The Variable Most Agent Systems Ignore

The second requirement is more subtle: time.

Most agent frameworks treat tasks as a sequence of frozen screenshots. The model receives an input, deliberates indefinitely, then outputs a step. But real software doesn’t freeze while it thinks. A payment page loads slowly. A banner animates over a button. A confirmation dialog appears only after an API returns. A message pops into a chat window mid-workflow.

These temporal shifts are the cracks where most agents fail.

Systems that represent tasks as event streams—rather than atomic prompts—create different behavior. Agents begin anticipating follow-up screens. They learn to wait appropriately. They recover more intelligently. They treat delays and state transitions as part of the landscape, not as errors.

Time turns agent behavior from brittle reactivity into something closer to operational intuition.

Measurement: RL Progress Without Replay Is Guesswork

The third requirement—reliable measurement—is often underestimated until teams hit the same wall: they improve a prompt, tune a policy, or switch model versions and feel progress, only to discover regressions weeks later in workflows no one thought to retest.

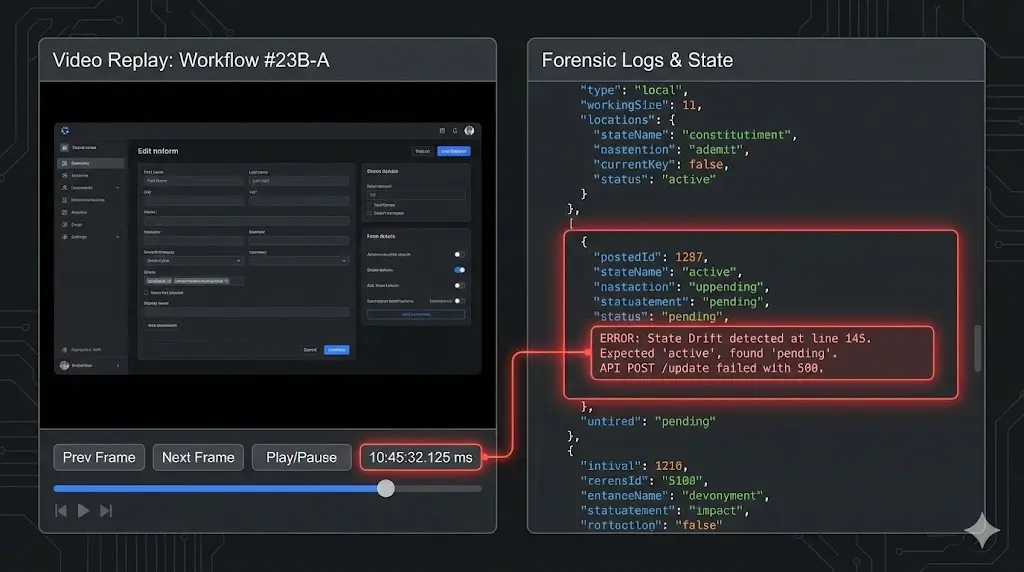

Most agent failures do not explode; they drift.

- An action fires slightly too early.

- A state transition is assumed before it actually completes.

- A response is read from an intermediate state rather than a terminal one.

These failures are often described using GUI metaphors, but the underlying issue is not graphical interaction. The same class of errors appears in API-driven agents: premature requests, misordered calls, stale state reads, and silent race conditions. Whether the action is a click or an API call, the failure mode is the same—the agent and the environment have lost temporal and causal alignment.

Without forensic logs and replayable episodes, debugging becomes guesswork.

Engineering teams are now treating RL evaluation like flight telemetry. Every episode must be recorded end-to-end. Every observation logged. Every action—GUI-level or API-level—timestamped. Every state transition reproducible. Episodes must be replayable not approximately, but frame-for-frame, across both frontend and backend interactions.

Without this, RL progress is anecdotal, not engineered.

Inside Abaka’s Approach: RL Environments That Push Back

As these industry patterns became clearer, different groups began rethinking what a real RL environment for agents should look like. Abaka’s approach emerged from repeatedly observing agents fail for reasons unrelated to reasoning—and entirely due to mismatches between agent assumptions and environmental dynamics.

At the core of Abaka’s system is an environment control layer that defines the authoritative dynamics of each RL environment: how time advances, how events are ordered, how state transitions occur, and under what conditions actions are considered valid. Rather than allowing agents to mutate the environment directly, every action is mediated through this layer, ensuring that observations, transitions, and outcomes remain temporally and causally consistent.

Surrounding this control layer is a collection of isolated, reproducible RL environments—sandboxed micro-worlds that run real applications, not mock interfaces. Each environment represents a fully specified episode space, complete with deterministic execution, comprehensive state snapshots, and a controllable notion of time. These capabilities allow episodes to be paused, accelerated for large-scale training, or replayed in full to analyze a single misstep.

Within this design, several principles directly address common agent failure modes:

- Explicit time modeling prevents fragility caused by asynchronous loading and delayed responses.

- Deterministic event ordering preserves causal structure in concurrent or multi-step workflows.

- Transactional state transitions prevent silent drift across long-horizon tasks.

- Ground Truth–anchored outcomes ensure that rewards and evaluation are tied to observable end states rather than heuristic judgments.

A verification layer continuously evaluates each episode against these Ground Truth outcomes and ties successes or failures back to the exact states and transitions that produced them. When a failure occurs, the entire episode can be reconstructed—every observation, action, and state transition—until the root cause becomes clear.

The result feels less like a conventional test harness and more like a coherent world model for agent learning. In these environments, agents do not merely execute actions; they acquire timing awareness, causal understanding, and recovery behavior that only emerge when the environment pushes back.

Research Roots, Production Reality: From AREs to Real RL Environments

Much of the conceptual groundwork for modern agent environments can be traced back to academic proposals for Agent Runtime Environments (AREs). These frameworks outlined a clean vision for agent–environment interaction: isolated worlds, orchestrated event loops, and deterministic execution. On paper, AREs looked like the right abstraction.

But operational RL Environments—those that train and evaluate agents in real software—require more than conceptual correctness. They require durability over time.

This is where the industry’s split becomes clear. AREs were built for experiments. Abaka is built for production RL.

- In research, exact replay and audit logs are helpful.

- In production, they are non-negotiable.

- A regression that cannot be replayed is a bug that cannot be fixed.

- A run that cannot be audited is a learning signal that cannot be trusted.

Abaka takes the architectural ideals of AREs and extends them with the layers required for real-world reliability: deterministic time control that forces workflows into reproducible sequences; transactional semantics that prevent the subtle drift common in long-horizon tasks; comprehensive state snapshots that capture every meaningful mutation; and a full replay system that reconstructs entire episodes down to timing, perception, and decision boundaries.

This replay capability is not just about debugging. It is foundational to how verification and reward are designed. Over time, Abaka has accumulated practical experience in defining verifiable outcomes, aligning rewards with observable end states, and tracing failures back through complete episode histories. When an agent succeeds or fails, the system can attribute that outcome to specific states, transitions, and decisions—rather than relying on heuristic judgments or partial signals.

But the deeper divergence is not architectural. It is environmental.

Real agents do not learn from static scenarios. They learn from variety, consequences, and long-tail unpredictability—conditions that only emerge when environments are rich enough to push back.

This is why Abaka invests heavily in what is often the most overlooked component of agent training: the environmental library itself.

Within Abaka’s system, environments function as classrooms. Different categories cultivate different competencies—competencies that never emerge in prompt-only benchmarks:

- Information-rich applications (search, maps, academic portals) train agents to retrieve, filter, and reconcile sources under changing context.

- Messaging and social platforms force agents to handle concurrency, interruptions, and asynchronous human workflows.

- Creation tools—editors, design applications, IDEs—demand multi-step reasoning, revision, and persistent state manipulation.

- Transactional platforms introduce responsibility: actions with irreversible consequences, side effects, and strict verification requirements.

These distinctions are not theoretical.

In Abaka’s ecosystem, each environment category defines explicit, observable terminal states that can be verified against Ground Truth.

- A document is updated or it isn’t.

- A form is submitted or it fails.

- A booking completes or errors.

- A design artifact changes in precisely defined ways.

Because outcomes are verifiable and episodes are fully replayable, every environment becomes a reliable training signal rather than a loose playground. Success and failure stop being qualitative impressions and become quantifiable data points accumulated across thousands of runs. Over time, these datapoints reveal where an agent adapts, where it generalizes, and where it consistently breaks.

In this unified framework, Abaka AI becomes more than an agent testing suite.

It becomes a developmental ecosystem—one where agents grow through structured friction, measurable outcomes, and environments that respond with consequences instead of compliance.

And that combination— the demands of production RL, and the realism of verifiable, replayable worlds—is what positions Abaka at a different point in the agent landscape: not as another demo generator, but as infrastructure for agents meant to operate where software is messy, fast, concurrent, and constantly changing.

A Future Built on Realistic RL Environments

The era of flashy demos has done its job: it raised expectations for what agents could become. The next phase of progress will come from something less glamorous and far more foundational—the RL environments agents are trained and evaluated within.

Agents that grow up in richer, more volatile, more consequential environments do not merely imitate intelligence under ideal conditions. They demonstrate competence in the conditions that matter: unpredictable, asynchronous, long-tail workflows that define real software.

This is the shift Abaka AI is betting on: that durable agent intelligence will not emerge from bigger models alone, but from RL Environments that force adaptation, recovery, and learning through consequence.

Not demos.

Not toys.

But worlds that push back.